Speech prostheses

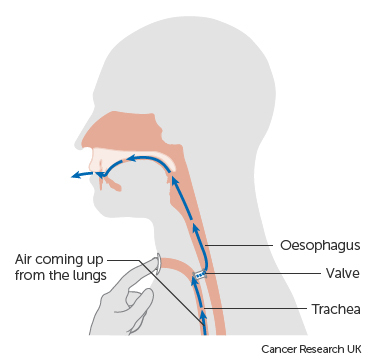

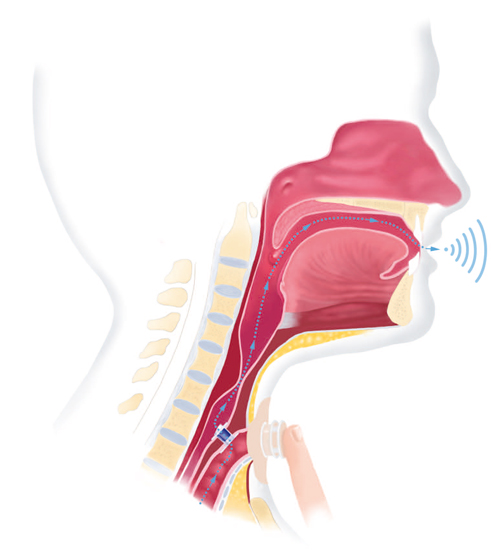

Speech prostheses, or voice prostheses, is a overall term for small, silicon one-way valves that are inserted into the trachea-oesophageal puncture of laryngectomy patients. The prosthesis not only safely divides the oesophagus and trachea, but also allow speech when the outside of the tracheostoma, the opening on the neck to allow air in, is covered with a finger or otherwise occluded. This is greatly beneficial to patients because it allows to communicate without the need to use either an Electrolarynx or Speech synthesizers.

Contents

Main characteristics

Oesophageal valves are made of medical grade silicon rubber and primarily consists of four parts: One-way valve, two flanges on each side of the tube, rigid valve ring in the middle of the tube, and a safety strap.[1] The safety strap is supposed to avoid the fall of the prosthesis to the trachea during the removal of the device. The two flanges are tracheal flange and oesophageal flange respectively. They vary in rigidity and size. Both depend on the valve being patient-changeable or not, with the latter being bigger in size and rigid so as to facilitate bigger longevity. Consequently, there are two types of prostheses, indwelling and nonindwelling.[2] The overall size, especially the diameter of the tube slightly differs among speech prostheses.[3]

The valve is inserted into patient's throat during the surgery, where is created a puncture between the posterior tracheostoma wall and oesophagus. The size of the puncture depends on the size of the valve, since the size of an each device slightly variates. The valve is only one-way, in order to prevent leakage of saliva, food or drinks to the air ways. The speech is produced, when the air, which goes through the valve, vibrates the mucosa of a larynx. Kazi points out, however, that the achievement of a voice after the trachea-oesophageal puncture is dependant at the further training of patients. The voice is not achieved automatically.[4]

There are several companies which manufacture trachea-oesophageal voice prostheses, the most renowned prostheses are Blom-Singer, Groningen and Provox.[5]

Patients which do not find trachea-oesophageal voice prosthesis suitable for them could use electrolarynx, speech synthesizers or oesophageal voice production.[6]

Historical overview

Eric D. Blom claimed that the first larengectomy restoration of a voice was made in 1931 by a patient using a red hot ice pick. The patient created a 'puncture' in the posterior wall of a tracheostoma to allow the air from lungs to enter mouth. Then, he inserted a goose quill in the puncture, in order to prevent the closing of the tract. The attempts of replications of this surgery were unsuccessful and the method was abandoned.[7] Usage of a valve for voice restoration was first described by a Polish otolaryngologist prof. dr. Erwin Mozolewski in the 1970s.[8] First commercially available oesophageal valve was introduced in the late 1970s, by Eric Blom and Mark Singer. It was considered a major step in voice restoration. Laryngectomy patients were required to learn oesophageal speech or use an electrolarynx to be able to communicate again before the introduction of this procedure.[4] In 1985, inserting oesophageal valves has been accepted as a primary procedure in the US.[9] Since then, the procedure became the de facto standard for post-laryngectomy treatment and voice restoration.[10]

Purpose

The purpose of speech prostheses is to return the ability to speak to patients after total laryngectomy.

Important Dates

- 1873 - Austrian surgeon Theodore Billroth performs the first laryngectomy.[11]

- 1931 - A laryngectomy patient made a 'puncture' in his throat.[7]

- 1972 - Polish-born otolaryngologist prof. dr. Erwin Mozolewski develops a way to give back voice abilities to laryngectomy patients with a small plastic valve connecting their larynx and oesophagus. The valve was officially unveiled on a international conference in Boston in 1979.[12]

- 1980s - The technique was popularized and made commercially available by an American company Bloom-Singer.[13]

Enhancement/Therapy/Treatment

Healthy individuals speak when they exalt air from their lungs through vocal cords placed in a larynx. The vocal cords produce a vibration, which is modulated to the speech by lips, jaws and tongue.[14] Patients, who underwent a total laryngectomy, have removed their larynx. This cause the loss of voice since the vocal cords are placed in the part of larynx which is removed. They cannot breath through their mouth or nose, but they are breathing through stoma, the small uncover hole in their neck. Trachea-oesophageal voice prosthesis could be installed during a total laryngectomy or in the further surgery. It aims to restore the ability to speak and bring the patient's quality of life as close as possible to the state before the laryngectomy. Patients have to cover they stoma, in order to speak.[15]

In comparison with oesophageal speech, the speech with trachea-oesophageal voice is easier to achieve, more fluent, more loudly and better intelligible. It also sound more natural than speech provided by elecrolarynx. The disadvantages of trachea-oesophageal voice are primarily the fact that the prosthesis has to be removed by physician and that the speech is not entirely hands-free.[16] There are, however, covers, which allow to speak hands-free.[17]

Ethical & Health Issues

Some patients may find the uncovered stoma embarrassing and would like to cover the puncture in their necks. There are several options to cover stoma: many tracheostoma covers, filters, and protectors are available on the market. These cloths or plastic covers range resemble the top of a turtle-neck or perhaps a baby bib and are available in different colours and designs.[18] The neck could be also covered by a scarf or light clothes. There are also various necklaces, which are available for women-laryngectomees.[19] The need to cover the tracheostoma is also medical one. The puncture opens the inside of the trachea to elements and liquids. A flexible cover and filter is usually put into the puncture to protect the trachea and provide moisture to inhaled air. In addition, certain covers could also help laryngectomees with trachea-oesophageal voice prosthesis to speak hands-free.[17]

Other exposure problem arises from the inside of the patients body. The one-way valve inserted in the trachea-oesophageal puncture is exposed to the body's defensive mechanisms and gets covered by a biofilm relatively quickly. This is offset by covering the valve with silver oxide that hinders unwanted biological growth on the valve.

Each speech prosthesis has a certain life time and has to be replaced hereafter. The life time of the prosthesis could be shortened, however, by several factors, as is inappropriate hygiene, reflux, trachea-oesophageal puncture tract dilatation, or when the prosthesis does not fit properly. The prosthesis should be cleaned properly and regularly, in order to avoid the rise of yeasts and microorganisms. The occurrence of either yeast or microorganisms badly affects the closure of a valve and could lead to a leakage of saliva or nutriment.[14] The valve can also get damaged by acidic reflux from the stomach. These effects can not be mitigated and the valve has to be replaced. Furthermore, LeBlanc and his colleagues claim that the risk of reflux might be increased by laryngeal therapy.[20]

trachea-oesophageal puncture tract dilatation

Simone E. J. Eerenstein and her colleagues argued that leakage could be also caused by the increase of the diameter of prostheses.[3] This claim was also supported by Eric D. Blom, the manufacturer of Blom-Singer voice prostheses, who pointed out several papers which demonstrate, that the prostheses with a higher diameter leaked more often.[21]

The spasm of pharyngeal musculus or swelling might caused that the patient after trachea-oesophageal puncture could not speak, but this complications could be overcome by medical treatment.[5]

Public & Media Impact and Presentation

TODO: Cancer support groups and websites.

Public Policy

trachea-oesophageal puncture considered primary practice and policy in hospitals???

Related Technologies, Projects or Scientific Research

Brush, flush, plug http://www.atosmedical.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/7962us_life-as-a-laryngectomee-brochure-201009a.pdf

TODO: Add list and pictures of specific valves.

https://www.inhealth.com/category_s/44.htm

http://www.webwhispers.org/library/tepprosthesis.asp

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voice_prosthesis

http://medind.nic.in/jat/t07/i4/jatt07i4p188.htm

References

- ↑ Atos Medical. Provox® Vega™:The Instructions for Use Clinican's. Atos Medical [online]. Available online at: http://www.atosmedical.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/10879_clin.-ifu-provox-vega_201512a_web.pdf (Retrieved 17th January, 2017).

- ↑ Atos Medical. United States Patent US 20090043386 A1. United State's Patent and Trademark Office [online]. 2012, Aug 7. Available online at: http://patft.uspto.gov/netacgi/nph-Parser?Sect2=PTO1&Sect2=HITOFF&p=1&u=/netahtml/PTO/search-bool.html&r=1&f=G&l=50&d=PALL&RefSrch=yes&Query=PN/8236007 (Retrieved 19th January, 2017).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 EERENSTEIN, Simone E. J. et al. Downsizing of Voice Prosthesis Diameter in Patients with Laryngectomy: An in Vitro Study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002 Jul; 128(7):838-41. Doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.7.838 Available online at: http://www.webwhispers.org/library/documents/Eerenstein.pdf (Retrieved 19th January, 2017).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 KAZI, Rehan, et al. Surgical voice restoration following total laryngectomy. Journal of cancer research and therapeutics, 2007, 3.4: 188. Doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.38991 Available online at: http://medind.nic.in/jat/t07/i4/jatt07i4p188.htm (Retrieved 24th February, 2016).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Cancer Research UK. Speaking after laryngectomy. Cancer Research UK [online]. Available online at: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/type/larynx-cancer/living/speaking-after-laryngectomy#tep (Retrieved 23rd January, 2017).

- ↑ BROWN, Dale H. et al. Postlaryngectomy Voice Rehabilitation: State of the Art at the Millennium, World Journal of Surgery [online]. 2003, 14 May. DOI: 10.1007/s00268-003-7107-4 Available online at: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00268-003-7107-4 (Retrieved 16th January, 2017).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 BLOM, Eric D. Current Status of Voice Restoration Following Total Laryngectomy. Oncology [online]. 2000, Jun 1. Available online at: http://www.cancernetwork.com/head-neck-cancer/current-status-voice-restoration-following-total-laryngectomy (Retrieved 19th January, 2017).

- ↑ MOZOLEWSKI, Erwin S., et al. "Arytenoid vocal shunt in laryngectomized patients." The Laryngoscope 85.5 (1975): 853-861.

- ↑ HAMAKER, Ronald C., et al. Primary voice restoration at laryngectomy. Archives of Otolaryngology, 1985, 111.3: 182-186.

- ↑ HUTCHESON, Katherine A., et al. Enlarged trachea-oesophageal puncture after total laryngectomy: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Head & neck, 2011, 33.1: 20-30.

- ↑ KAZI, R. A., et al. Christian Albert Theodor Billroth: Master of surgery. Journal of postgraduate medicine, 2004, 50.1: 82. Available online at: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/2074/1/jp04025.pdf (Retrieved 25th February, 2016).

- ↑ TARNOWSKA, Czesława. Wspomnienie o profesorze Erwinie Mozolewskim. Pomorski Uniwersytet Medyczny w Szczecinie [online]. Available online at: https://www.pum.edu.pl/__data/assets/file/0009/14868/Wspomnienie_o_profesorze_Erwin_7517.pdf (Retrieved 19th January, 2017).

- ↑ InHealth Technologies. Blom-Singer Historic Achievements Brochure. InHealth Technologies [online]. 2008, Aug. Available online at: http://www.inhealth.com/v/vspfiles/pdf/brochures/Blom-Singer_Historic_Achievements_Brochure.pdf (Retrieved 19th January, 2017).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 BROOK, Itzhak. The Laryngectomee Guide. American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery [online]. 2015. Available online at: https://www.entnet.org/sites/default/files/LaryngectomeeGuide.pdf (Retrieved 19th January, 2017).

- ↑ Laryngopedia. Trachea-oesophageal voice prosthesis (TEP). Laryngopedia [online]. 2017. Available online at: http://laryngopedia.com/tracheoesophageal-voice-prosthesis-tep/ (Retrieved 19th January, 2017).

- ↑ SERRA, A. et al. Post-laryngectomy voice rehabilitation with voice prosthesis: 15 years experience of the ENT Clinic of University of Catania. ACTA otorhinolaryngologica italica [online]. 2015; 35(6): 412-419. Doi:10.14639/0392-100X-680 Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4755057/ (Retrieved 23rd January, 2017).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Atos Medical. Provox HMEs and speaking valves. Atos Medical [online]. Available online at: http://www.atosmedical.com/laryngectomy/living-with-laryngectomy/the-provox-solution/ (Retrieved 20th January, 2017).

- ↑ Luminaud Inc. Luminaud: Speech, Voice and Communication Products. Luminaud Inc. [online]. Available online at: http://u.b5z.net/i/u/10204675/f/CF0615pdfbw_c.pdf (Retrieved 17th January, 2017).

- ↑ GARDNER, Warren H., HARRIS, Harold E. Aids and Devices for Laryngectomees. Arch Otolaryngol 73(2) [online]. 1961: 145-152. Doi: 10.1001/archotol.1961.00740020151003 Available online at: http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaotolaryngology/article-abstract/1766151 (Retrieved 17th January, 2017).

- ↑ LEBLANC, Blake et al. Increased Pharyngeal Reflux in Patients Treated for Laryngeal Cancer: A Pilot Study. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery [online]. 2015, Aug 25. Doi: 10.1177/0194599815601026 Available online at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0194599815601026 (Retrieved 23rd January, 2017).

- ↑ BLOM, Eric D. Some comments on the escalation of tracheoesophageal voice prosthesis dimensions. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003 Apr; 129(4):500-2. Doi:10.1001/archotol.129.4.500-a Available online at: http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaotolaryngology/article-abstract/483807 (Retrieved 20th January, 2017).